Today, I decided that I would put up an essay I wrote six years ago. The idea came up when a friend was discussing the concept of wealth. There is truth in the saying that the grass is not always greener on the other side. Oh…and appearances can be deceiving.

BEHIND THE IRON GATES AND MANICURED LAWNS

by JC Crumpton

My parents may not have had much faith in the Chicago Public School system when we lived up there for my first through fifth grade years. I can say this with a fair amount of confidence because my father had four part-time jobs in addition to training recruits at the Great Lakes US Navy Recruit Training Command just to put me, and later my two younger sisters, into a private school. In order to spend time with my father during those formative years I often went to work with him.

I spent some late nights wielding a pricing gun against endless bags of egg noodles and cases of Kraft Mac-n-Cheese at the commissary. Some weekends I played Space Invaders or pool, watched the Chicago Cubs, or learned all sorts of new and colorful language while my father worked as a short order cook at the Staff Lounge on the base. Occasionally I would stay up through the late hours helping him deliver Sunday newspapers—more often than not I would fall asleep midway through the route, usually after the 7-11 stop. But the one job where I spent the most time with him was when he worked as a groundskeeper for a wealthy family that lived in a stone house behind an iron gate.

People like me only saw places like this mansion in the movies. The main entrance opened to a marble-floored foyer with a wide, sweeping staircase and a huge crystal chandelier larger than our living room. It hung from the domed ceiling towering high enough overhead that my nose would have bled if I had climbed up there. But it also had a cozy library with a comfortable window seat that overlooked the gray stone-cobbled patio and garden where I spent much of my time while my father mowed the lawn or tended the hedges. The couple had two kids—a boy close to my own age and a girl just a bit older. They always seemed to be gone at boarding school or camp.

Their mother may have been lonely with her kids usually absent and husband always working because she would bring me hot chocolate in the winter and lemonade during the summers. Looking back on it through a lens of years and maturity, she always seemed sad as if she had lost something important to her. She would sit in the library or in the lawn furniture overlooking an expansive field and talk to me. And me being the typically-attentive eight-year-old would listen and not remember a word of what she said. I met the children only once that I can recall. The boy and I played in the yard and explored the woods, but he acted preoccupied as if playtime were something foreign to him. His sister never left the library and never spoke to me when we came back, only smiling a quick little smile.

After four-and-one-half years in Chicago—during which time we experienced the unforgettable Blizzard of ’79—we moved back to Southern California, living with my maternal grandparents while my father spent six months in Iceland without us. To supplement his income as an English teacher at Garden Grove High School, my grandfather worked as a groundskeeper for one of those opulent mansions up in the hills just off a curvy, tree-lined road.

My favorite part was the Jacuzzi up on a little rise that overflowed into a stone channel where it tumbled down the slope into a beautiful pool with clean water and dark blue, hand-laid tiles. I almost drowned in that pool, but that’s a different story.

The couple’s only child was a boy my own age, but just as the children in the Chicago mansion came home only occasionally, he too seemed to be away at boarding school or at camp. And his mother also walked around with a sad look on her face most times I visited. One weekend my grandfather and I actually saw the boy at home between one camp and the next or boarding school. His mother suggested he and I go up to his room and build models. They owned a beautiful house with more mahogany and walnut than the marble of the mansion in Chicago but still very lavish and surprisingly bright with all the broad windows and California sun.

When I stepped into this boy’s room, I thought I had entered into a hospital examination facility. It possessed no sense of ownership—no fifth-grade art project hanging on the back of the door, no favorite G.I. Joe action figures scattered across the built-in desk, no rumpled covers where he had rushed to make his bed before scrambling downstairs to watch cartoons, and no homemade name plaque on the door. I can only describe it as being very sterile, devoid of personality and maybe even life. We built a couple of models, but he seemed not to enjoy the experience saying that his results weren’t good enough. He did smile briefly when I told him that he had done a good job.

In high school, after we moved to Arkansas from Iceland because my father had retired from the Navy, I started mowing lawns to supplement my allowance income of…nothing. We couldn’t be considered well-to-do in Arkansas those first few years as we qualified for the free-lunch program at school. I never realized it at the time—or if I did, I just buried it. Not even when my parents bought my school clothes at a flea market did I figure it out. Only when I started earning money on my own, buying what I wore to match what I saw in Gentlemen’s Quarterly did I realize we were poor.

As an adult, I paid someone to mow my lawn until the kids were old enough to perform the task. But I have never lived behind the iron fences. I mow my own now. Too expensive.

The grass may seem greener on the other side to the tired mind, but I have seen behind the iron gates and manicured lawns. I was never afraid to have fun with my father and have never shrugged from playing with my own children. Looking back through time and trying to see behind the filter of an adolescent mind, the fathers that built the wealth to have those expansive houses presented inattentive personas on those rare occasions they were home. The mothers that managed those estates and the kids that lived there only on a part-time basis always appeared sad, empty, as if they lacked something vital, something to fill the holes in their hearts.

Life behind the iron gates always looked desirable in the movies or on the much smaller screen—like Dallas and Knots Landing. But I’m glad for those late nights atop piles of newspapers packed from the floorboard to the top of the seats in the old blue Ford LTD. I’m grateful for the long walk through the ice and snow with my father while the car had its transmission replaced and I experienced hot chocolate with marshmallows for the very first time at the restaurant in a Travel Lodge hotel.

The manicured lawns and trimmed hedges were beautiful because my father and my grandfather made them so, but they lacked the life of a beating heart. My heart beat fierce and strong behind those flea market shirts, and I wouldn’t change it for all the iron gates in the world.

WHAT I’M UP TO

WRITING: Two major projects going on right now. 1) I have the skeleton and detailed outline of Bishop completed and am working on fleshing it out. It will be a historical horror set during the Viking settlement period of Greenland. 2) The sequel to Field of Strong Men is almost complete.

FICTION: Still working on The One-Eyed Man by L.E. Modesitt, Jr. There is some political intrigue developing in the tale—kind of a mystery.

NONFICTION: Started rereading books and articles about Vikings, including some Icelandic sagas.

TELEVISION: Started watching on NefFlix My Country: A New Age. It is a South Korean television series (subtitled), and unlike other series on the streaming service, the entire series is not available all in one grand upload. Two episodes per week come out. It is a historical fiction that covers the transition of the Goryeo to Joseon dynasties. It is incredible. Betrayal, war, intrigue, sword fights, love, misunderstandings. I haven’t seen something like it in quite some time.

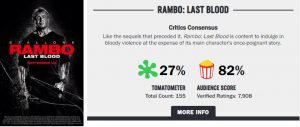

MOVIES: The critics hated it. The audiences loved it. The consensus on Rotten Tomatoes reads, “Like the sequels that preceded it, Rambo: Last Blood is content to indulge in bloody violence at the expense of its main character’s once-poignant story.” All that is true. But today’s audiences do not go to the theater to ascertain whether or not the main character has had a sufficient arc either toward or away from redemption or revenge or whatever. The audience members are not like the critics in that they are not trying to apply everything they learned in over-priced, useless Film History college courses. They want to be excited. They want to be entertained. They may even want to cry and worry a little bit—not realizing that it is the arc a character goes through that often creates that connection making us tear up. All-in-all, they don’t want to resent shelling out $12 for a ticket.

Rambo: Last Blood did that for me. And I have taken several criticism courses that I cannot apply to my daily life. But I went to the cheap $6 night at Malco Theaters. The audience in the theater enjoyed it by my estimation. Everyone waited until the montage of previous Rambo films finished and the lights came up before leaving. Now if it were in book format, I would have wanted a little more meat to the story. As it stands…I was entertained. And I didn’t need a lot of back story because I have seen all the entries. I know the character’s history and arc.

Loved your essay. How we identify wealth is such an important discussion. Right up there with playing fair. You ring true.

Thank you.