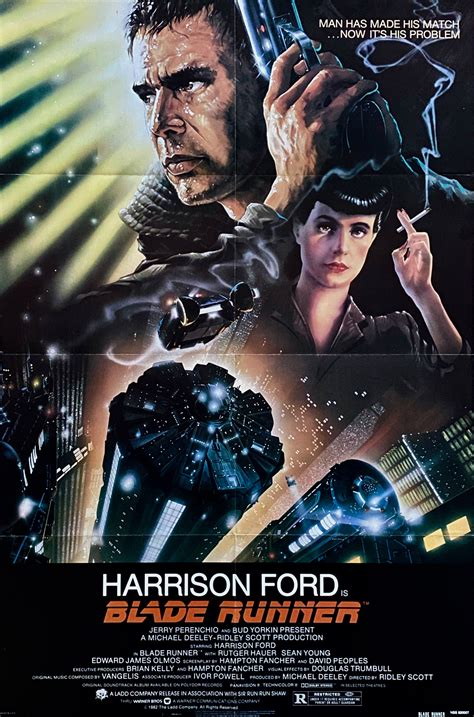

The critic Ben Sherlock does not like the Ridley Scott-directed science fiction movie Blade Runner—adapted from Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? When I read the piece he’d written, calling it slow paced and boring in comparison to violent action-filled films thrown at us today, I almost spewed my hot chocolate across my desk.

I sat there wearing a twisted, horrified expression. My breath came in hesitant gasps. The film I knew well enough to annoy my wife by speaking with it should, in my opinion, be held at the Smithsonian Institute in a protected position of prestige and honor. I’m throwing down the gauntlet. This calls for a rebuttal.

Ever since I first saw the film, it has held the venerated status of being my favorite movie. Of all time. Easily. Even though I stand firm in my opinion, Mr. Sherlock writes correctly when he said the movie has a “bleak, depressing tone.” Given its content and source material, that atmosphere is by design.

Mr. Sherlock lists ten points describing his thoughts on why the classic neo-noir film proves to be a difficult watch 42 years after it first appeared on the movie screen. He has some valid points. But, as Sean Connery’s iconic character Captain Raimus told Jack Ryan in the film The Hunt for Red October, his “conclusions were all wrong.” Good article, but I am going to refute each point.

- Slow, cerebral pacing gets pretty boring at times.

The material presented in Blade Runner should be allowed to mull over in the brain and heart, giving it time to develop and ripen. If single-take action continued through the whole runtime, the audience would not have a moment’s repose to understand the intent of both the characters as well as the author.

Mr. Sherlock correctly asserts “audience’s attention spans have gotten shorter.” Do we reward this by consuming more meaningless drivel designed to distract rather than present ideas our brains should contemplate? I’m going to go out on a limb and say we should be allowed to think about what we see on the screen.

The character Eldon Tyrell best encapsulates the reason we should not be distracted when he tells Harrison Ford’s Rick Deckard, “More human than human is our motto.” This is the central point of both the movie and its source novel. The pacing of the movie is perfect in order to understand it.

- Rick Deckard isn’t a very likable protagonist.

Again, Mr. Sherlock hit the nail on the head with this statement. He’s not wrong. No one should find Deckard to be a person they want to entrust with caring for their families. Deckard is a killer. He hunts down replicants, androids that are physically and often psychologically indistinguishable from humans.

Remember the motto? More human than human. What Deckard does as an occupation is undeniably inhumane. It’s like the neighborhood bully I had growing up in Chicago who poured kerosene on a nest of bumblebees and lit it on fire. Why? For what purpose?

Deckard is not likable at all. He shouldn’t be. But the theme of the movie and book is what makes us human. The character arc—the growth and change experienced—is what makes a work memorable and relatable. We are supposed to see ourselves in Deckard. What makes us human? Can we change?

- Doesn’t have as much action as its premise would suggest.

Mr. Sherlock is again right. There isn’t a long sequence of witless, eye-candy action exploding all over the screen. Heaven forbid we should ingest something presenting a different motif than the zombie-like existence much entertainment gives us. Don’t think. Just stare. Consume. Buy. Do not reason as to the why.

The design of the movie and source novel do not need non-stop action. How would that propel the story forward? When writing or filming a story, if the writer can remove a scene and the story remains unchanged, it is superfluous to the purpose of the piece. It should be removed.

- Ridley Scott is more interested in showing off Blade Runner’s special effects than telling its story.

Okay. This is the first point I feel Mr. Sherlock got all wrong. Well…mostly wrong. I’ll agree with that since the movie is visually beautiful in its own right. However, I think Scott intended such a striking contrast. We see Daryl Hannah’s Pris hiding in a pile of garbage.

The movie visuals enhance the story. What we see on the surface often hides what waits below. A story depicting the inhumanity of humans needs to be beautifully realized. What is the pretty picture hiding? Much of the movie takes place in the dark. No stars—even though the background advertisement blimps roaming the city talk about life being grand and perfect out beyond the current world.

- Blade Runner’s most interesting character is its villain.

Mr. Sherlock nailed this one. 100-percent accurate. However, we should look below the surface. Who—or what—is Roy Batty? According to the profiles Deckard receives on the escaped replicants, Batty is a combat model. Designed and programmed to kill. Batty is a mirror placed in front of us. He gets us to look at ourselves.

No one character is perfect in this movie. Batty murders Tyrell. He kills innocent J.F. Sebastion—the man displaying the most empathy for the escaped replicants. He tortures geneticist Hannibal Chew. He is not a good person. Interesting? Very.

Character change and development makes a good story. Grander transformation gives a good story the potential to become great. Such is Blade Runner. Batty, a combat model replicant that kills without remorse or second thought, delivers a soliloquy at the end of the movie that exemplifies the transition the character goes through. At the end, he realizes how essential life is.

- Deckard’s treatment of Rachel makes for an uncomfortable watch.

Two in a row. He is unequivocally correct in this assertion. After an extensive empathy test, Deckard discovers Rachel is not human. But remember the motto? How the bounty hunter treats the most-complex and “human” of all the replicants is that mirror shoved in front of our faces. Again.

The goal of a good movie or story is character change. Deckard transforms by the end of the movie, and his primary goal is the protection of Rachel, not hunting and killing more replicants. But Mr. Sherlock is correct. The protagonist’s treatment of Rachel is horrendous.

- Is a classic example of style over substance.

Mr. Sherlock tells his readers that Blade Runner “oozes style,” and it does in spades. But his line supporting this point, to me, is the point. “For a movie about what it means to be human, Blade Runner doesn’t have much humanity.”

Exactly. Director Scott made a paragon of perfection in this regard. Hampton Fancher and David Peoples wrote a perfect script to depict the inhumanity of human behavior. No need to mention the novel’s author Philip K. Dick. A lot of his work made into films is about that very same subject. Total Recall. Minority Report. Impostor. The Adjustment Bureau.

- There are too many versions of Blade Runner to choose from.

I’m not going to argue this point. I agree completely. In my opinion, the international theatrical release is the best version. Even with the voiceovers no one else likes.

- Blader Runner’s futuristic L.A. lacks the diversity of the real city.

Yes, Los Angeles is one of the most ethnically “diverse cities in the United States.” I enjoyed Edward James Olmos’ and James Hong’s roles in the movie. A lot can happen in forty years, making it hard to predict the future.

- Blader Runner has a really bleak, depressing tone.

I won’t disagree at all. Mr. Sherlock says that is the “main thing” making the movie so tough to rewatch so many years after its release. To me, that makes it a nearly perfect movie. It deals with tough issues. How can we consider ourselves human when we are so inhumane?

It throws up a dark mirror for us to take a good, hard look at ourselves. Are we heading in the right direction. The flying advertisement blimps constantly announce that “Off-world opportunities await you.” The movie and story are asking us, why do we try to escape what we’ve done? Why don’t we try to fix what makes us inhumane? We are capable of it. Deckard and Batty both change by the end of the film.

Conclusion.

Mr. Sherlock wrote an insightful article. I enjoyed it. I just disagree with his conclusions. We are coming at it with two different sets of eyes. It’s bound to happen.

Personally, I feel Scott captured the essence of what Dick wanted to portray when he wrote Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Both beautiful and dark. Surreal and grounded. Pristine and filthy. Blade Runner has always been my favorite movie since I first saw it.

But there is one thing I didn’t like about it: I was too young to see it when it first came out and never had the chance to see it on the big screen. That changed in 2017, when they re-released the film to theaters prior to the launch of the Blade Runner 2049 sequel. Now, I am content.

You can check out the mentioned article at https://screenrant.com/blade-runner-1982-movie-harsh-realities-rewatch/#blade-runner-has-a-really-bleak-depressing-tone.