April 16, 2024

My wife and I have noticed over the years since my severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), I can lose my mind over rather trivial things. A little over a year ago, I was involved in another motor vehicle accident. A car struck my vehicle in the rear, spun me, and rolled me. I never lost consciousness but my Nissan Rogue I’d won in 2018 by hitting a hole-in-one during a golf tournament ended up being a total loss.

I remember hanging there looking out the front window at the other cars driving by on SE 14th Street in Bentonville, Arkansas. Smoke drifted from somewhere, so I reached up and turned the car off. It turned out to be from the airbags—thankfully, they deployed and did their job. The view out the driver’s side window revealed nothing but grass.

My head hurt. My sides ached, stabbing with each breath. But my biggest concern was my notebook and pen. These two items hold places of greater value to me than any car. I unbuckled myself and started frantically looking for my stuff.

The driver from the other vehicle raced over to my wreckage and asked, his brows furrowed with concern, “Are you okay?”

The notebook lay on the window-ground beneath me, so I picked it up. Then, I nodded to the man and replied, “I can’t find my pen.”

My heart raced. An impending sense of doom fell over me. I didn’t understand why, but I knew with certainty the world would end if I could not find my pen. The injuries didn’t matter. I needed my pen. It was like blood to me. Words flowed from it onto paper and something intangible became real. Relief flooded through me, imbuing me with a sense of tranquility and belief that everything was all right in the world when I found it wedged under the accelerator.

My body hurt. It took a fire engine crew to get me out of the vehicle. The doctors held me overnight for observation because of a possible brain bleed—turned out to be scar tissue from a mishap over three decades earlier. My source of transportation lay in a twisted pile at a scrap yard. A couple weeks later, the insurance adjustor told me he’d never seen a car with as much damage where the person had not been hospitalized multiple nights. Through all of it, all I worried about was my pen and notebook.

Over the years, I have misplaced my pen. When I do this, panic ensues. I can’t help it. My mind races as I frantically search everywhere. I interject a little sarcasm here because my wife usually finds it in an obvious place where I should have looked—the beside drawer, my desk in my library, or the console in my car (the new-ish car).

She has told me if the world suddenly descends into utter chaos, she wants me to be beside her because of how calm I remain. If I lose my pen? In those situations, she would prefer to be as far from me as possible. I am unreasonable. The world could be ending, and I’d pour myself a nice glass of lemonade. Should I be unable to locate my pen or notebook, I know the world is ending. Without a doubt. Chaos descends over my reality, throwing me into full panic mode.

Over time, my wife and I have realized why this is. The pen and notebook are my greatest compensatory strategy when dealing with the impairments resulting from my severe TBI. If I have those tools on my person or within grasp, I have a sense of control in my life. Without them, I am adrift in a tumultuous sea, tossed by giant waves in the dark.

To help me lock facts and events into long-term memory, I have a mantra: hear it, write it, read it, see it, say it. This works for me. This past weekend, I met a couple in a restaurant in Springfield, Missouri. Lauren and Jeff have a one-year-old daughter. He works in tech and was in the army. She just finished school and will be starting a chiropractic practice. He has decided to return to school. They both will be chiropractors and practice together. I wrote this all down. I read it back once. I have not looked at it again.

That is what the pen and notebook do for me. They represent my greatest tools—my greatest weapons in living with the impact of a severe TBI and its myriad difficulties. Now, ask me what I had for dinner last night, and I will give you a blank look.

When something serious happens, I remain calm—as long as I have my trusted tools. During the first decade of our marriage, my wife had a seizure. I moved the furniture and called 911. No big deal. The first time I lost my pen, she thought she would have to put me in a straightjacket.

The pen and the notebook have been my greatest compensatory strategy since my time in rehabilitation. But just like any skill, it must be used to be effective. I go ballistic when I lose them because I am at the mercy of chaos. They are my security blanket.

March 29, 2024

Years after the accident that put me in a coma for four days and rehabilitation for six months, I have retired from working 28 years in the corporate world, traveled to 46 of the 50 states, survived cancer and two massive blood clots, and published newspaper articles, poems, and books. Considering that my heart stopped twice and an MRI of my brain more resembles Swiss cheese than anything else, a person could be forgiven for looking at me and saying, “That’s great. You’ve had a full recovery.”

That is great. I have the folks at Timber Ridge Rehabilitation and the compensatory strategies they taught me to thank for giving me the chance to live as normal a life as possible. I say “as normal” because there isn’t a normal thing about my life. In addition to the therapists and staff at Timber Ridge, I have a loving family that searched diligently for a facility to help me deal with the ravages of my life caused by the severe traumatic brain injury (sTBI). But most of all, I give my wife credit for my success in life.

When people tell me I’ve had an excellent recovery, I tell them thank you. However, my internal voice is screaming, everything you see is an illusion. The exterior I share with the public does not accurately represent the turmoil I experience every waking day caused by extreme blunt trauma to my gray matter.

What I display does not account for those moments when I am feeling anxious. It does not include the days I have not gotten enough sleep, exercise, or proper food. It does not consider those days when I am sick or overwhelmed by external and internal stimuli.

The people I meet—even friends and colleagues whom I’ve known for years—do not get to see that side of me. My wife does. She suffers the horrors of what I am like when I do not have my compensatory strategies engaged. Impulsivity, inappropriate behavior, memory deficits, physical infirmities, egocentrism, difficulty in compromise, lack of emotional control. She sees it all.

She and I took a long drive yesterday. We went to visit Timber Ridge in central Arkansas. She wanted to see the facility that helped me develop the skills I need to get through my day. They helped me understand that I am not the damage to my brain. While we were visiting with some of the staff, I listened to her side of it. She engaged with the people that work with TBI survivors every day.

It turns out my wife, my spouse, my mate goes through as much turmoil as I do because of my head injury. This is why I am thankful for her. They talked about TBI survivors making inappropriate comments and how she will at times go behind me apologizing because, in her words, I have no filter.

One of my greatest faults is my arrogance. If it were not for Chrissi, I would not have continued to utilize the compensatory strategies I learned at Timber Ridge. She has made me want to be a productive part of society as well as our relationship. As my work and research continues for this memoir, I realize that without the continued support of a loving family and people surrounding you, a head injured person faces a long and difficult road.

January 7, 2024

I have some good news. I have some bad news. Next, I would normally ask you to choose which you want first, but I’m going to take that choice from you. Here comes the bad news: welcome to the world of living with a severe traumatic brain injury (sTBI).

You don’t get to push reset. You cannot pick up where you left off. Your life is going to go in a direction different from the trajectory it had originally travelled. The road will have potholes. The shoulder will be crumbling and fragile, not offering much in the way of safety where you can pull off and relax before continuing your journey.

For someone who has suffered from an sTBI, she or he will be rehabbing for the rest of her or his life. Things get more manageable. They don’t get better. Spontaneous recovery of damaged neural clusters in my brain does not occur.

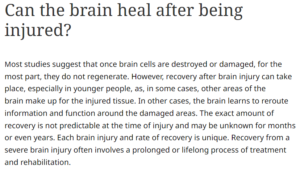

My neurologist told me while perusing an MRI film of my brain—something more resembling an avant-garde piece of art on the subject of Swiss cheese than a complicated neural processing center—other parts of my brain had adapted to take over what the dead parts once did. Then he added the caveat, “They won’t be as good at it as the original.”

This came to my attention last night while my wife and I prepared for bed. I had just returned from attending a write-in in Springfield, Missouri and was in the middle of telling her one specific thing about it. Suddenly, I stopped.

I could not remember what I was going to say next. There was nothing there. I looked up at her and shook my head. Then, I walked out of the bedroom to go brush my teeth. From the corner of my eye, I saw a sad look come over her face. She has seen this for over 25 years, almost half my life. It doesn’t get any better. I cannot choose when or what I remember or forget.

Now the good news. As I said a little while ago, I will be rehabbing for the rest of my life. This means I have to keep in place the organization and structure I learned in neurorestorative rehabilitation to remain an active participant in everyday life.

In my back pocket, I keep a little notebook in which I write down grocery lists, ideas I’ve thought of, pieces of a new poem or story I’m working on. What I didn’t write down is the story I had been telling her. It is worn and much used. It is a part of me.

A positive saying adorns the cover of the notebook: “Every day is a fresh start.” How true that is when you have an sTBI. But that’s the good news. Having suffered severe brain damage is not the total sum of my life. When I utilize the deficit management strategies taught to me at rehabilitation, the casual or moderate observer would not realize I suffered often-incapacitating deficits.

Hey…every day is a fresh start.

December 22, 2023

Have you ever walked into a room and forgotten why you entered it? How about meeting someone and not being able to recall their name minutes later? These could be considered age-related memory loss. A common enough phenomenon considering we give it credence by accepting it.

I have learned the human brain creates new cells no matter our age or level of decrepitude—I’ve always wanted to use that word since I first heard it in the movie Blade Runner. My theory on age-related memory loss is that our brains get filled with stuff over the years, and we think of some things as trivial. It’s probably been happening all our lives, but we just obsess about it as we get older. The fear of dementia looms large in our minds the more times someone notifies the fire department when we light our birthday candles.

Imagine now, if you will, those same memory hiccoughs happening daily ever since you were the ripe old age of eighteen. After writing those first two paragraphs, I went back and looked at the update from two weeks ago. Guess what? I’d written about memory impairment already. Let’s change focus.

How do I get around those hiccoughs? Scheduling and organization. Those two elements have proven key in my being able to live a normal life. As normal as you can expect when your neurologist tells you he is surprised you are as high functioning as you are considering the amount of damage to the old gray matter.

I live by my daily schedule. No, I do not have every minute of every day planned out for me. What I do have is a list of tasks that need to be completed. When I first entered head injury rehabilitation, that task list included such simple things as making my bed, brushing my teeth, getting dressed, or taking a shower.

As I progressed, those lists became more detailed. As the morning routines became habit, they dropped off the list. But traveling to other countries sure makes things difficult. Good thing my wife travelled with me recently to Europe or I might not have put on deodorant or taken a shower.

Speaking of my wife, we balance each other. I have been diagnosed as having ADHD. In my youth, I lived by the moment, embracing each idea as it came into being. For the last 33 years I have been unable to do that. It would cause immense frustration. Then everything I and my cognitive therapists worked so hard on would just have to be thrown away.

My wife does not like her day to be regimented out. She likes some spontaneity in her life. When we go on a trip, everything to her is a pleasant surprise. In order for me not to lose my sh**, I plan events.

When we went to Iceland, every stop, every location, every place to spend the night was planned. She had no clue until we stopped at a beautiful waterfall or woke up early and saw the sun rise over the black sand beaches of Vik. Same as in England, Scotland, and France.

Living with a head injury is a difficult thing. But a life resembling what society calls normal can be achieved through a structured life using a schedule. That might be too boring for some, but it is a lot less stressful to a head injured person than living life in a chaotic situation resembling the pandemonium going in our brains.

When we went to Iceland, I planned for us to stay in a camper van as we traveled the Ring Road. My wife added a little disorder by insisting on hotels. So, I can adjust after all. Given enough time. It took me a couple nights before the frustration at having my plans changed faded. But I must admit, those hotel beds were a lot more comfortable.

December 8, 2023

Sometimes I get frustrated. Not all those times are with me. Having experienced a severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), it is not unusual for me to forget something. Last month, I knew I needed to run up to my wife’s work and tell her something in person. She works twenty minutes from the house. I got in my truck and drove up there to give her this important information.

I walked into her place of employment and found her right away. When she came up to me, her head cocked to the side as I’m sure she tried to imagine what had brought me up there. I opened my mouth.

“I forgot why I came up,” I said. “I know it was important enough for me to drive twenty minutes to tell you in person. But right now, there is nothing in my head.”

Of course, that opened me to all kinds of jokes about not having all my marbles or that my noodle was scrambled. She doesn’t say them. I make those jokes about my own condition.

After a TBI, the brain often has difficulties shifting short-term memories into long-term for later retrieval and review. If I don’t write an appointment down, I run a good chance of forgetting it. The easiest way to think about this is that I cannot remember to remember.

This proved a sticky point early in our marriage when I would forget to fix lunch or dinner for the kids while my wife worked. It might mean I neglected to bring my own lunch to work. Taking medication must be done to a system of alarms. Birthdays, anniversaries, and appointments are all written on the calendar.

While at rehabilitation, I learned compensatory strategies to help me with my memory deficits. These include writing it down and reading it aloud to myself. Recording it in my day planner. Over the years, I have developed a mantra: Hear it. Write it. Read it. See it. Say it.

When I first came out of the coma, I could read a line of text and would repeat the same line because I could not remember that I had already read it. That would have made me frustrated as well…if I could have remembered that I had forgotten.

The frustrations stem from sad children because you forgot their birthdays, missed appointments, or lingering bronchitis due to forgetting to take antibiotics. My frustrations with others occur because they may feel they are being sympathetic when they are unintentionally patronizing me. We don’t need sympathy. Head injured persons need empathy.

They may say, “Oh, I forget where I put my keys all the time.” Or, “That happens to me more now than it did when I was young.”

That’s the problem. This isn’t as simple as age-related memory loss. I have had poor memory-making abilities since I was 18—over three decades ago. Typically, I just smile and go on my way. I’ll probably forget it happened anyway.

November 18, 2023

Post-Traumatic Amnesia (PTA) often occurs in conjunction with brain injuries. When the brain is injured, fighting for its life, it rarely forms new memories. That’s why an athlete can get a concussion during the first part of the game and not be able to remember what happened during the rest of it.

This happened to me after my accident. I suffer from minor retrograde amnesia in that I cannot recall 2.8 miles of road before the accident happened. I suffer from drastic PTA in that I cannot recall anything I did or experienced up to six months after the cerebral insult occurred.

Medical personnel determine the level of a traumatic brain injury (TBI) by using the Glascow Coma Scale. It measures three different categories: eye opening, motor response, and verbal response. A typical oriented and healthy person will receive a score of 15. I received a 3. This meant that my eyes would not open on their own, not with verbal stimuli, and not as a reaction to pain. I had no motor response to pain stimuli, and I presented no verbal activity. According to this scale, I suffered from a severe TBI.

According to another scale called the Rancho Los Amigos Scale, I had a score of 1, meaning that I had no response to sounds, movement, or touch, and resulted in me being in a deep coma. The severity of a TBI can also be determined by the length of PTA. Anything greater than 4 weeks is considered “extremely severe.”

In my recent exploration of my TBI, I came to the realization that I am extremely blessed. Studies have shown that PTA of a prolonged duration in TBI patients increases the burden of care for the TBI patient by medical professionals and family or friends.

My coma lasted four days. My brain swelled to where they almost had to open my skull to give it room. My PTA duration lasted around six months. By all means, I should not be able to hold down a job and perform at the level I do. My neurologist read my MRI a little over ten years ago and told me, upon seeing the damage still obvious to my brain, “I am surprised you are as high functioning as you are.”

Some of the emotional and behavioral problems a TBI survivor can exhibit include frustration leading to verbal or physical outbursts, impulsivity, engaging in risky behavior, diminished social skills, and confused self-awareness. This can result in depression, mood swings, and anxiety.

I am not saying I do not suffer from any of those. In fact, I am prone to depression, and I have discovered that my outlet is not through drug therapy. Rather, I exorcise the darkness through poetry. Since I am able to lead a functional life—I’m not saying it is a bed of roses because I have been run the gauntlet more times than I care to recount—I feel it is my duty and honor to help family members understand the changes and difficulties their head-injured persons are going through.

In the 30+ years since my cerebral insult, I have realized it can be a scary world out there. Especially to those of us that wake up strangers in a world we should know.

November 9, 2023

The brain is a marvelous but often fragile thing. Without it, we wouldn’t be who we are. Without it, we would be unable to perform the simplest of tasks. What impacts does a person experience when that vital organ is damaged?

I have been working on a memoir about my own experiences with a traumatic brain injury. As I mentioned in the writeup for the 5th of this month [see dated entry below], a neurologist told me after seeing an MRI of my brain it surprised him I am as high functioning as I am. Some people who know me better may have a differing opinion. Since I am “high functioning,” I thought I had this responsibility to let others know the difficulties TBI survivors face every day. Perhaps, I will be able to help a family member understand why their loved one doesn’t seem the same after the injury. And why they deserve to be loved still.

But since I am “high functioning,” how extensive was the damage if I am able to write a book about the topic? And what gives me the audacity to say I can speak for other TBI survivors?

My heart stopped twice. My brain swelled to the point the doctors were preparing the operating room to open my skull. When I first entered a comatose state, my Glasgow Coma Scale score was a 3. Anything below an 8 is considered a severe brain injury.

I was completely nonreactive to any type of stimulus, including pain. One way they test this is to put a pencil between your fingers or toes and squeeze them together. The body cannot help but to react involuntarily unless the brain is unable to receive or interpret those nerve signals.

Family members need to understand what TBI survivors go through every day of their existence for the rest of their lives. I found this fitting quote during my research. This is why I write it.

“The worst part is, with traumatic brain injury, people can’t see it. And they see

on the outside that I move around. I do this, and I do that, but they don’t see the

struggle inside: the memory loss, the struggles to remember, the struggles to

forget.” – TBI survivor

November 5, 2023

Around 12 years ago, I had an appointment with a general practitioner because I was experiencing foot drop. I was tripping over flat floors. Seriously, I would be walking down a perfectly level hall, and suddenly, the tiles would grab me and try to throw me to the ground. The doctor ordered an MRI, and I suffered through the terrible elevator music and bad jokes from the technician.

The results gave him pause, but not me. My brain looked like Swiss cheese with a flurry of lesions. He sat me down and solemnly informed me his medical knowledge had determined that I suffered from MS [Multiple Sclerosis is a degenerative disease that occurs when the myelin sheaths of the nerve cells in the brain and spinal column are damaged]. I didn’t panic. My wife did, but I remained calm.

I had one simple question: “Could this be a residual effect of my traumatic brain injury?”

He responded, “No. I have several MS patients whose MRIs manifests exactly like yours.”

“Thank you, doctor,” I said. “I’m going to get a second opinion.”

I left the clinic and promptly made an appointment with a neurologist less than a mile away. He pulled up the MRI films and studied them, nodding and occasionally mumbling to himself. Brilliant doctor. Finally, he looked up.

“You don’t have MS,” he informed me.

Relief flooded through me. My wife actually sighed and maybe even cried a little—my memory is a little foggy.

He took the time to explain why he had come to this conclusion. “None of your lesions are active. If they were, they would be a bright white. Yours indicate that other parts of the brain have adapted to fill in for what the damaged parts controlled.”

This reassured me, relaxing me. But then he continued.

“Actually, I’m surprised you are as high functioning as you are in consideration of how much damage there is.”

What?

“The parts of your brain that have taken over for damaged areas work, but they may not work as well as the damaged portion did. This explains the foot drop.”

The brain is an amazing thing. But what it cannot do is take me back to the condition in which I existed prior to suffering the traumatic brain injury. It can adapt. It cannot be made new. This isn’t a difficult concept to understand when you think about it. When you suffer a deep laceration on your arm, you will very likely have a scar on your healed skin—but hey, they’re like tattoos but with better stories.

This experience drove home the point I have been trying to tell people for years: there is no such thing as a full recovery from a head injury.

I have been working on the first chapter this week. It still doesn’t have a title. The focus is on the changes I and other TBI survivors experience compared to our pre-injury selves. We can’t go back to being who we were with any certainty. Some will have more pronounced changes than others. Some will have little. There is no way to predict this. All I know is that I see the world differently than I did the first two decades of my life.

That last sentence in the clip from the article hits home: a lifelong process of treatment and rehabilitation.

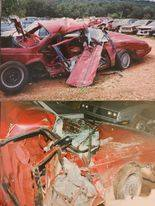

My heart stopped twice during the early morning hours on the 19 th of May 1999. I didn’t want it

to, but I didn’t have much say in the matter. The tractor trailer loaded with 40 tons of charcoal

barreling through the passenger door of the car in which I rode had the final word.

A piece of metal jammed itself into the side of my head and severed my temporal artery. Something ripped a chunk of bone out of my forehead. Every single rib on my right side fractured. My right hand was crushed, and my right knee shattered. The accident resulted in a coma, my brain swelling and receiving significant trauma.

ripped a chunk of bone out of my forehead. Every single rib on my right side fractured. My right hand was crushed, and my right knee shattered. The accident resulted in a coma, my brain swelling and receiving significant trauma.

After six months in rehab participating in physical, occupational, and cognitive therapy, the physical injuries healed. The impacts of the traumatic brain injury still plague me over thirty years later.

When people see me, they cannot perceive the turmoil and anguish that churns beneath the surface. I often hear, “You look like you recovered well.” What few realize is that no one ever fully recovers from a traumatic brain injury. I will experience effects from the accident for the rest of my life.

I can walk. I can talk. I can read and write. What I cannot do is live the normal life I lived before

the night a 40-ton missile exploded into me. What my family and friends cannot do is have a

relationship with the person I was before the accident. It changed me in more ways than most can

fathom.

The effects from the traumatic brain injury plague me and will continue to do so to the end of my days. They will also impact the way friends and family who knew me before the accident react to

the changes they see in me.

This is for the family members of traumatic brain injury survivors. We are not the people we

were before. We deserve to be loved for who we are now, not just who you remember us to be.